Salabhasana is said to resemble a locust at rest, however this invigorating pose will seem anything but restful. Since locusts, the migratory stage of grasshoppers, are known for their movements and swarms, when I practice the pose, I envision a locust in flight as my back works to give me upward and forward momentum. Recently, I saw the dramatic footage of a locust jumping. It leapt, not only straight upwards off the ground from its large hind legs, but it threw itself backwards fully extended in the air and reached its front arms overhead towards the sky, an act of force and grace.

Salabhasana is one of the first backbends we learn and is often referred to as a beginning backbend. While it doesn’t require the same endurance and mobility in the joints as backbends where we have to push upwards against gravity or stand on our arms or legs, Salabhasana requires a burst of strength. Since we don’t rely on the support of our limbs to lift us in Salabhasana, we need to contract the muscles of the back and abdomen and thus we cannot hold the pose for as long as some of the other backbends. The few moments that we do manage to hold the pose are vigorous and focused.

B.K.S. Iyengar interprets Patañjali sutra I. 20 to state that virya or vigor is required to break through “spiritual complacency.” As yoga practitioners it is easy to think we have attained our goal by lifting the chest off the floor in one pose or by reaching the hand to the floor in another and to slacken our efforts. Striving for perfection in asanas is not for the sake of competition with others or ourselves or for the achievement of an aesthetically pleasing form, it is part of the lifelong practice of seeking deeper knowledge with the ultimate goal towards freedom. Iyengar states that instead of basking in delight over their achievements, advanced yogis “adopt new means to intensify their practice with faith and vigor (virya)…” He says that virya “stands for valor and power in the sense of physical and nervine strength.” When it is applied to yogic pursuits with alignment serving as the mind’s shepherd, the physical power of virya can lead us down the meditative path of liberation from disturbances.

As you practice Salabhasana, you will find that the initial energy required to get into the pose can be intensified to seek further extension, expansion, power, and freedom. Once you discover how and where to channel that strength, Salabhasana will rejuvenate you. The stimulation derived from the effort is not agitating but is pointed and leads to calm mindfulness. The absorption involved in maintaining the spurt of energy for Salabhasana focuses the mind. You will find that even though it is an invigorating pose, you are left feeling tranquil and alert.

OPENING UP ON TOP

As in all backbends, we need to be able to open the chest well for Salabhasana. In this pose the chest broadens and the shoulders roll backwards, all of which requires flexibility in the shoulder and strength in the upper back. This standing variation trains us to coordinate the actions of the upper body.

Stand in Tadasana with your feet hip-width apart. Place a belt loop tied wider than shoulder-width around your wrists behind your back. Keeping your legs straight, lift the sides of the ribcage upwards and broaden the top of the chest from the collarbones towards the outer corners of the shoulders. Without disturbing the legs or the rest of the torso, begin to reach your wrists back away from the legs. As the arms move backwards roll the shoulders back and down towards the hands and lift the sides of the chest higher. Press the wrists against the belt and push the belt backwards.

Now that your shoulders are opening, see if you can further lift the arms and chest by moving the shoulder blades downwards away from the head and towards the chest as you cut the bottom edges of the shoulder blades towards the spine. You should feel the spinal muscles in the upper back are firm and supporting the fullness of the upper chest.

The work of the arms and shoulders should not distort the rest of your body. Keep the thighs back so that the pelvis and abdomen don’t swing forward and lift the abdomen upwards towards the chest. If you raise the arms too quickly, you will find that the shoulders roll forward and the upper back lifts up into the neck, so go slowly to coordinate the actions of your shoulders, shoulder blades, and chest with your arms.

If you have tight shoulders and they automatically roll forward when you take your hands back, try widening the loop of the belt. The sensation should be one of separation between the arms and upper back: the further back the arms and shoulders go, the further the chest (especially the armpit region) moves forward. Just when you think you have stretched fully, try engaging the back muscles further and releasing the upper back away from the neck and see if you can lift the chest and arms a little more.

BELLY DOWN, LEGS DOWN

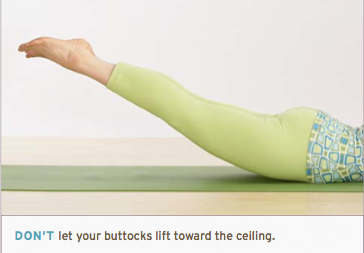

When you first lie down, extend the whole front of the body so that the space between the abdomen and thighs is extended on the floor. Elongate the front of your thighs towards the feet and lengthen the feet and toes back away from the head. Press the tailbone down into the floor so that the buttocks and front pelvis don’t rise.

With your forehead on the floor extend the arms by the sides of the body, lift the outer corners of your shoulders up away from the floor, roll the shoulders back towards your wrists, reach the wrists back and broaden the chest. Exhale and lift your chest, head, and hands off the floor with the arms parallel to the floor. Cut the bottom outer corners of the shoulder blades towards each other to pull the shoulders back to open the chest further. As you reach the arms further back, move the shoulder blades down the back away from the head so that the neck remains long. The buttocks muscles have to work to keep the tailbone and buttocks from lifting. Extend the inner edges of the legs back towards the feet. Apply a little more virya to these actions to raise the ribs from the floor. After a few moments come down and rest.

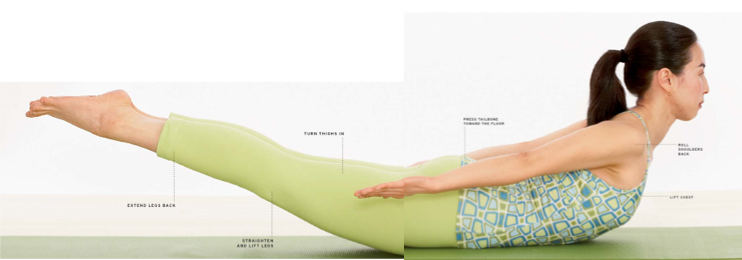

LEGS IN FLIGHT

Now you will incorporate the lift of the legs. When the legs rise from the floor, the inner legs have to work even harder to remain in line with the outer legs and the buttocks have to work more to keep the tailbone nailed to the floor to prevent the buttocks from jamming into the lower back. The legs may wander apart from each other and turn out so turn the thighs inward and draw them closer to each other. Reach through the big toes; don’t let your feet turn outward. When you incorporate all of these actions, your muscles may feel tired but the lower back should not ache.

Lengthen the front of the body on the floor as in the previous variation so that you feel that no part of the front body is wrinkled or stuck on the floor. Begin again by lifting the outer shoulders away from the floor so that the upper back and shoulder blades move away from the neck making space to lift your head without any congestion around the base of the neck.

As you press the tailbone and buttocks into the floor, extend the abdomen towards your head. On the exhalation, lift the chest, arms, head and legs from the floor. Reach the chest forwards and extend the arms and legs back. Keep the legs straight, turn the front of your thighs inward and lengthen the inner edges of the legs towards the big toes while the buttocks remain firmly pressing downward.

Even after only 20 seconds in the pose, you will feel the intensity of effort to maintain the virya of a leaping locust throughout. Not only does Salabhasana have an energizing effect but it also cultivates a state of calm awareness. According to Patañjali the yoga practitioner, through concentration, meditation, and absorption, is able to free consciousness from the spell of time. We normally see ourselves as subject to the chronology of past present and future but when we can become completely absorbed in a single moment, the ordinary time-bound operation of the mind ceases; we can experience timelessness and glimpse freedom. This is yoga.

SIDEBAR:

In Salabhasana the postural muscles in the abdomen and back are toned. The strength in the back, opening of the chest, and movement of the tailbone prepares you for the practice of other backbends such as Dhanurasana, Urdhva Mukha Svanasana, Ustrasana, and Urdhva Dhanurasana.

The abdominal strength built in Salabhasana not only supports your back but can also help in the performance of inversions, abdominal poses such as Navasana and arm balances. The work of the shoulder blades and upper back as well as the position of the arms is similar to Sarvangasana and can aid in the practice of that as well as other inversions such as Sirsasana.

Since Salabhasana requires the quick ignition of many muscles, it is best to practice other poses beforehand to prepare the body and brain for the effort. Standing poses such as Trikonasana,Virabhadrasana I and II, and Ardha Chandrasana help to awaken the spinal and buttock muscles. If you find it difficult to keep your legs from turning out in Salabhasana, the work of the back leg in Virabhadrasana I will also help you to learn how to turn the thighs in while pressing the tailbone down.

Salabhasana is a great pose to address asymmetries in the body. Because the back muscles are in a strong state of contraction, you may be able to observe that one side of the body works harder than the other. Use the extension of your arms and legs to help activate the weaker side of the body and create equal length on both sides of the back.